Student study fosters wave of focus on increased access to filtered water

The popularity of single-use plastic products and containers results in nearly 80 percent of bottles ending up as litter, clogging landfills with two million tons of plastic, all of which can take thousands of years to decompose. Many elect to use bottled water for reasons such as health or taste, and are unaware that 40 percent of bottled water sold in the U.S. is actually tap water.

Fueled by these truths, graduate students in Dr. Erin Dreelin's water policy course partnered with Michigan State University's Sustainability department to view the issue of plastic waste generated on campus through a new lens. Sean Barton, project and event coordinator for MSU Infrastructure Planning and Facilities (IPF), was the project liaison between the department and the students in Dr. Dreelin's course. Their collaboration led to a survey of over 1,200 members of the MSU community, revealing important information about drinking water habits.

"We evaluated why people opt for bottled water versus tap water. While the tap water was completely safe, meeting or exceeding all federal minimum standards, it left more to be desired in regards to taste. We looked at that and saw an opportunity—we needed to make people aware of these filtered drinking fountains," says Barton. Results of the survey provided MSU Sustainability with enough knowledge to adapt their approach in order to meet the needs of those on campus. Using the university as a living laboratory ensured that decisions were made based on data concerning campus drinking water habits, and that key stakeholders were included in the project.

This research partnership even contributed to a tangible change: IPF is using the data to begin installing filtered water stations on many drinking fountains across campus. The increased availability of water refill stations will encourage the MSU community to purchase a reusable water bottle, ultimately helping them save money and reduce waste reaching the landfill—all while drinking water that meets their taste standards.

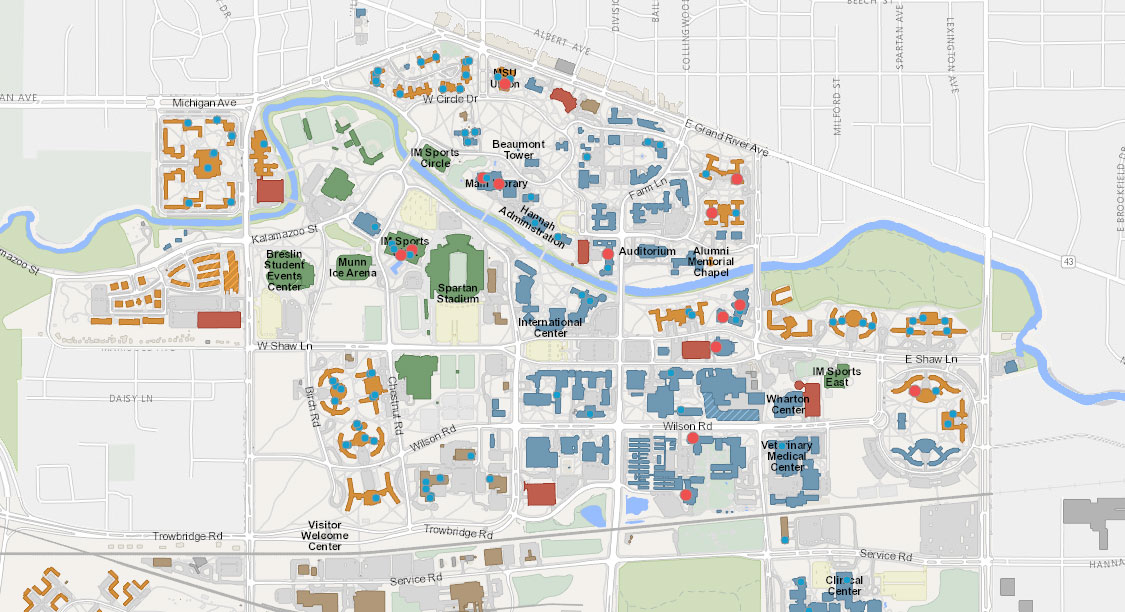

Red dots on this campus map represent high-impact areas where new water stations have been or will be installed in the future.

Melissa Rojas-Downing, one of the graduate student researchers involved in the project, noted that the results of this study reflect the potential of students to make an impact at MSU. "Students should view this as an example illustrating that these kinds of issues on campus present an opportunity for research. We saw challenges with the quality of the water, so we tested that very issue. Students can identify problems across campus and serve as champions for improvement," notes Rojas-Downing.

Barton recalled skepticism that the survey would ever occur, but his perspective was changed by the dedication of Rojas-Downing and other student researchers. "Every time there was a road block, they would come up with new solutions. Both enthusiasm and apathy are contagious, and their enthusiasm spread, making everyone involved want to work harder to make change happen."

Barton's later partnerships with other classes mapped all the locations of drinking fountains on campus and found that 126 of the 768 drinking fountains currently have filtered water for reusable bottles. 33 high impact areas were identified through analysis of traffic patterns and the number of people using each building. IPF began installation in the spring of 2016 and is prioritizing these areas, but funding will continue for many more installations beyond these. Additionally, Barton noted that Infrastructure Planning and Facilities, in collaboration with Residential and Hospitality Services, is establishing standardized signage for these stations, helping to draw attention to the filtered water and create a recognizable brand.

The students who administered the survey hoped it would foster an ongoing dialogue between the MSU community and the university about drinking water preferences. But the results of the study generated so much more than a conversation—look for newly installed filtered water stations as the impact of this student-led initiative spreads across campus.

For more information about the changing infrastructure, visit the IPF website.